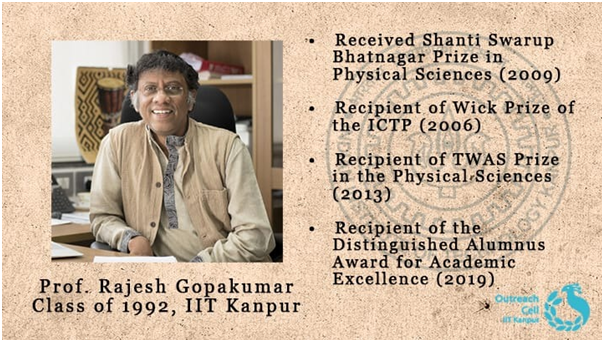

Distinguished Alumni Interview Series: Prof. Rajesh Gopakumar, Director, ICTS-TIFR

Outreach Cell, IIT Kanpur brings you the 3rd edition of the Distinguished Alumni Interview Series. We interview people who have contributed exceptionally to the society after graduating from IIT Kanpur and bring their inspiring life stories to you.

This edition brings you the story of Mr. Rajesh Gopakumar, who received the Distinguished Alumnus Award for Exceptional Academic Brilliance in 2003.Mr. Rajesh Gopakumar is an eminent theoretical physicist whose pioneering work is helping to decode the baffling laws of quantum physics. Currently, he serves as the director of the International Centre for Theoretical Sciences (ICTS-TIFR), Bangalore. He was previously a professor at Harish-Chandra Research Institute (HRI) in Allahabad, India. His work on a simplified version of string theory led to the discovery, with Cumrun Vafa, of the Gopakumar–Vafa duality and Gopakumar–Vafa invariants. He is a recipient of several prestigious awards and recognitions including the Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar Award for Physical Sciences in 2009.

Here are some excerpts from our conversation with Rajesh Sir-

1. It is considered that "college life is a golden life" because it is one of the most crucial parts of our life. My parents usually say that the freedom I enjoy at this stage of life, may not be that easy to come by once I start working. We hear many exciting stories about earlier days of campus life. So would you like to share some of your fondest memories of IITK?

Yeah. This is very true. In some sense, I think those are very formative years for people because those are the years when they are making the transition from being teenagers to adults. During this time, your views on the world, life, yourself, your goals, and so on, everything is being formed. And I think IIT Kanpur played a significant role for me in that. Firstly, there was an environment that was conducive to the kind of things that I held crucial, like pursuing knowledge in the sciences, etc. Secondly, I was fortunate to have many wonderful friends who shared many of the goals and ideas. We used to talk a lot and explored life and found out new things together. I think there was never a more intense five-year period of my life than the one I had in IIT Kanpur.

I especially remember, of course, long conversations with friends, but also the campus, as it was a little different from the present. I used to be in Hall 3 in my first couple of years, and the space outside Hall 3 beyond the mess and so on was just open. There were none of these new hostels or even the New SAC. There was only a football ground, so till the campus boundary, it was just open land, and one could go for long walks. You could go to the canal on the other side as there was only some barbed wire and you could go very easily through it. You didn't have all these walls and too much security. So I used to go for cycle rides to the canal, the airstrip, and nearby places. I grew up in Kolkata, and for me coming to a place that had all these open spaces was a very liberating experience. So from that point of view as well, I found that environment amazing. Even though we were in a little bit of a bubble - we hardly went to the city in those days - but we lived in that bubble, and it was a great time.

2. It has been observed that generally for students extracurricular activities and academics don't go hand-in-hand. But as your profile reflects just the opposite. You not only excelled in academics (secured AIR 1 in IIT-JEE and academic performance was also one of the best), but were also involved in different cultural activities. How did you manage to balance out both?

Honestly, I didn't really think in those terms of balancing. I just did what I enjoyed. I enjoyed studying mathematics and physics from a fairly early age.

Even before I joined IIT Kanpur, in my school, I was very active in quizzing, and so on, as for me, it was all knowledge and learning exciting things wherever they were. It was just doing what I enjoyed. And I think that rule of thumb has never let me down. If you enjoy doing something, spend the time on it - it's worth doing it - and then other things will work out. So I used to read a lot of literature and other things. Even in IIT Kanpur, courses I took in Humanities were mostly in Philosophy. So I was very interested in some of these topics apart from Physics and Mathematics, and then quizzing and other things were all part of the fun that I had along with my quiz partners with whom I'm still in touch. Altogether, I don't really remember thinking whether I'm doing too much of this stuff, too little of that, just managed. So, the rule of thumb was 'Do whatever you enjoy', I mean what you feel fulfilling, what can also sort of enrich you and what makes you grow as a person from inside. I think those are the important things in life, and now 30 years later it is much more clear to me. I feel, that's how one should lead life.

3. Are you still in contact with any of your college friends?

Very much. I think some of those friendships are probably among the deepest friendships I have had. In fact, I'm more in touch with my IIT Kanpur classmates and friends than many of my school friends or people afterward whom I met. So the experience of living together in those very frugal circumstances of the hostels and managing through those years, I think, creates a bonding, which has been very lasting. Of course, we all went our own ways after IIT Kanpur, many of us went to the US, and many people stayed in India. So in the early years, I think we had less contact because of the lack of these Social Media communication tools, and the internet itself was not so common in the early 90s when we had all dispersed. But gradually, with time and as people have also grown, I think I meet my friends now in the US, India, and so on very often. When I went back for the 25th reunion at IIT Kanpur itself, I met many again, about a hundred of our batchmates, about one-third of our batch had shown up. So it was a good occasion, and I also met others with whom I made it a point to be in touch regularly. I am in touch with some of them professionally also in many ways.

4. After completion of B.Sc at IITK, you did M.Sc from IITK itself, Ph.D. from Princeton, and were a Research Associate at Harvard University. All of them are very prestigious institutions. How was your experience in all three of them? And in what ways were they different from a student's point of view?

Of course, life is different in each of these surroundings since they come at different stages in your life. As I said earlier, the stage at IIT Kanpur is when you transform from being a teenager to an adult. I think that's a critical time in anyone's life, and where you spend it, how you spend it makes a big difference. So this is why the five years that I spent afterward at Princeton were not as formative as the ones at IIT Kanpur. They were very important for me professionally because, in some sense, a Ph.D. is like an apprenticeship where you're really going from being a student to a practitioner of research, and you pick up the necessary mental and temperamental qualities needed for doing that. Princeton was a very small town, and I don't think that I had a big circle of friends, but it was mainly spent in first getting used to the US environment. I also think that mostly it was getting myself immersed in my particular area of work that I was pursuing in theoretical physics. So my Princeton years, in some sense, were very boring compared to IITK years. I mean, it was sort of not so eventful in a certain way, though, of course, like always through life, you are continually growing with experiences and meeting new people and they are all enriching.

I spent roughly four years after that at Harvard, and in some ways, those were the best years in the US that I spent because Harvard is in a town - Cambridge in Massachusetts, next to Boston - and it's part of the city. So you get exposed to a different kind of life, and there was always a very vibrant culture in Cambridge. You're not just part of a university but also a part of the town - many events are going on there, and you hear many kinds of talks on different areas and meet other friends who are not necessarily in academics with you. And in a way going from India where you're used to having a lot of people around you to Princeton was a little bit strange because, like most US towns, you hardly see any people there. Even though it's a university, in the campus you see people, but outside that there’s little. But in Cambridge, it was quite the opposite. There were very nice bookstores, movie theaters and everything where you could get exposed to a lot of other things. So for me, those years in Cambridge were very charming.

But as institutions and especially in my area, I think I couldn't have been at places where I would have gotten better exposure and training. My advisor in Princeton was also one of the premiere scientists worldwide, and I learned a lot from him and afterward my mentors in Harvard as well. So professionally, these were wonderful experiences for me. And the 9-10 years that I spent in the US, professionally, they helped build me. So that was a different kind of experience.

I should add that as a student, you have to kind of take courses, solve some assigned problems and so on. But as a researcher, you have to learn how to phrase questions and make headway in the subject that was already developed a lot by many people. So it's a different kind of skill from that of doing exams and stuff like that. So these skills are very important to make this transition from being a student to a researcher. It is also a little bit of a difficult period for everyone if you choose to research, but I think being at these places helped me in the long run.

5. You opted for Integrated MSc in Physics after securing 1st rank in the qualifying exam for IITs, which is something quite uncommon. So, were you sure at that time that you wanted to go for research and higher studies instead of doing a job after Btech?

Well, I actually didn't plan to go to IIT. I think I decided I would study Physics and mathematics sometime in my 10th or 11th standard. So sometime around 10th exams, I was planning to study Physics in some college in Kolkata, where I was growing up. But then one of my seniors from IIT Kanpur informed me about its physics department and how there were so many good teachers and that it has an excellent five-year program. So then I decided to write the IIT qualifying exam because I was very clear that I didn't want to do engineering, which is why I didn't give any of the other conventional engineering exams. So my only thought was that if I go to IIT, I will try to go for this physics program. I had anyway been pursuing my independent studies in Physics and Mathematics. So for the IIT exam, I just needed to brush up or sort of pick up some of the things in chemistry, which was not something I had spent too much time on. So that was the only thing I did, and then I don't know how I came first. I mean, it just happened, I guess. But coming first didn't change my idea of what I wanted to do. So, I was very clear that I wanted to do research in mathematics and physics, which appealed to me as a lifetime goal. I had read some of Einstein's writings when I was in school, and somehow, that appealed to me - the idea of spending one's life in the quest of scientific knowledge.

6. I guess in those times, parents and social pressure would have wanted you to pursue engineering or sciences. Instead, you got into physics. Why? As a theoretical physicist, what is your motivation (apart from mathematical beauty) to make a theory with no experimental basis till date)?

I know - everyone around me wanted to do engineering or medical, and that's what parents and the whole social pressure was about. In class 10, when I expressed to my parents my interest in physics, they were a little worried but, I think, trusted my judgment. And as I said, even after the IIT exam, many people told me to take computer science. Because at that time, IIT Kanpur was the desired place, and all the top rankers used to go for Computer Science at IIT Kanpur. So that was the place where people wanted to go, but I was never so keen on computer science though some of its mathematical aspects perhaps appealed to me. As I said earlier, I was very influenced by some of the books I had read, not only about Einstein's writings on physics but also the Feynman lectures and George Gamow's books on physics and even some of the mathematics books also. So I wanted to do something in that field only. So the idea of trying to understand the mysteries of the universe was something that was very strong in my mind. I watched the documentary 'Cosmos' by Carl Sagan, which was another very formative experience. I liked both mathematics and the idea of physics of trying to penetrate the fundamental laws of nature. So in a way, I guess I had more of a theoretical bent because of my interest in mathematics also.

As to the second part of the question, why I choose to work on something like string theory with no experimental basis till date? I should say that I actually was a bit of a skeptic myself. When I went for my Ph.D., I wanted to do theoretical physics and Quantum Field Theory, which is the framework in which most fundamental forces are described, but not necessarily do String Theory. Because, even though there was a lot of hype about String Theory, I was not necessarily convinced by it. And most of my Ph.D. thesis was also not on string theory but more on Quantum Field Theory. But as I learned more of it - I picked up on String Theory and Quantum Field Theory both in Princeton - I realized that there are some very compelling aspects about string theory which make it the very natural generalization of Quantum Field Theory, which is one of our most successful physical theories till date. But Quantum field theory is unable to incorporate gravity in a very consistent way; however, string theory does it remarkably. The years afterward, I lived through the mid-90s and late 90s, where some remarkable developments in string theory happened, which made me feel even more confident that string theory, although still very far from connecting to experiments, is nevertheless something very compelling. It is actually now connecting different areas of theoretical physics. So string theory has become like a framework, which goes beyond Quantum field Theory but also includes it and makes remarkable statements about both gravity and Quantum field Theory and vice versa translates one to the other. Due to which I think now a lot of non-string theorists and physicists who don't use string theory are coming around to the idea that there is something remarkable here. And so this is one of the reasons which keeps me motivated to study String theory.

And I believe that while it may appear that the experimental predictions and the range of phenomena that string theory talks about, this may be outside experimental reach right now, but I think human ingenuity is such that they will come up with smart ways to find this. After all, the gravitational waves predicted by Einstein were discovered only a hundred years later in 2015 after being predicted in 1915 from his general theory of relativity. So I think one has to take the long view, and I personally find many compelling things about string theory that I feel that it is already saying many things about theories that we already knew but in a completely new way. And of course, I think it is also telling us about things we don't know like quantum gravity, quantum properties of black holes and so on. I could go on about that for a while, but I think it's quite remarkable how string theory is now connecting with many other physics areas.

7. If we talk about the world rankings, IITK (or all Indian universities in general) is quite behind as compared to Princeton or Harvard, where you did your post-doctoral or Ph.D. study. So what changes do you think IITs need to make in their curriculum to compete with the topmost universities in the world?

I must say that in terms of undergraduate education, probably IIT Kanpur gave me an undergraduate education in physics, comparable to the best places in the world. The teachers we had were brilliant people who had themselves studied in some of the best universities in the US at Princeton, Columbia, Chicago and so on. And they came to IIT Kanpur with a lot of idealism, and they communicated that to the students whom they taught, and they taught in a very fresh and clear way. So we had many outstanding teachers in the physics department at that time, and I learned a lot from them. So much so that when I went to Princeton for graduate studies, I saw that some things I had learned, which some of my fellow students, people who had come from the undergraduate program at MIT and other places, had not learned, so it really felt that I had gotten a very good education. There were, of course, many things we could have done more. I mean, I think our experimental facilities at IIT Kanpur could have been better at that time. Some of the equipment had become quite old and had not been operational. But I think the teachers were fantastic and that is very important.

However, I guess one drawback as compared to Princeton and Harvard, where there were, of course, excellent teachers as well, was that they were very active in research and not only they have very good teachers but also they were doing some cutting edge research. This whole idea of having research universities where the cutting edge research is done by people who are also teaching undergraduates at the same time, I think that's something in India, we have to really shape our system so that we can do that because then some of these undergraduates who come through that program will not only get a basic grounding in the concepts through the courses but also develop an aptitude for research and some of the skills needed for research already as an undergraduate. And even if you do not do research later in physics or anything else, I think that helps you in building your analytical skills in whatever profession you may choose to do, whether you're an engineer or a physicist.

Having that exposure to the tools of research, how you approach problems, analyze them, break them up, and so on and put them back together with all these tools these skills, I think, is very important to impart to undergraduates. I believe universities like Princeton, Harvard, MIT, Caltech, and others do this very well, which we could pay more attention to in IITs. Of course, the US has the other advantage that it has access to some of the world's best minds, both as graduate students and as professors. So they are able to attract some of the best faculty from around the world to come and teach, which in India for a variety of reasons is still difficult to do. Nonetheless, I think we can do more even within the constraints under which we operate.So I would say that there is a very good base on which to build but having a little more global approach and the idea of being at the cutting edge of research and feel driven to do new research, I think this enhances the atmosphere of the University and makes the place feel as if it is not just training people, but it is participating in the creation of new knowledge. And that feeling communicates itself to undergraduates when they are in a place which they feel it's really an active participant in creating new knowledge. So I think that is a very invaluable feeling, and I hope we can grow that in the IITs much more than we currently have. Of course, having a global population of even students, faculty, and so on also helps in this because it brings in a lot of diversity of thinking and attitudes, whereas otherwise we tend to become a little too monocultural, which is never very healthy for intellectual diversity.

8. One of the most famous theoretical physicians, Freeman Dyson, was critical of the Ph.D. system in academia. What are your views regarding the Ph.D. system? Because at times, it becomes extremely prolonged, and pursuing it requires a lot of patience. What are your suggestions for future generations regarding this?

I'm aware of Freeman Dyson's views. I mean, he was at Princeton all his life not at the university, but at the Institute for Advanced Study, which was a place I have spent some time afterward also. Of course, he was a remarkable genius, I think, he was also a bit of a contrarian. He himself never got a formal Ph.D., and by being at the institute for advanced study, he didn't have to take on any students, in fact, sometimes, worked with some undergraduates, but that was about it. So he had this view, which I respect - I think it has certain merits - that there is a tendency that, like in any institutionalized structure, getting a Ph.D. and the whole thing becomes a bit like a factory after a little while. There's a kind of an assembly line of students, and you take them through the steps, and they become very similar in certain ways, but I think Freeman Dyson was rebelling against that kind of attitude which turns out students in a kind of an assembly line. He wanted to create a space for more independent-minded researchers and people who would not fit in so much into the conventional research framework of going through Ph.D. and postdoc and tenure-track faculty etc. But it's very difficult to implement that on a large scale, and I think that the Ph.D. system is one of the best we have, with all its faults and limitations. We can always try to improve it. But there should be the kind of space that Dyson wanted to carve out for independent thinkers, and hopefully, some of the institutions will think of innovative ways to create that.

It is true that pursuing a Ph.D. indeed requires a lot of patience. But I think if you really want to be a lifelong researcher or even just if you're going to develop these specific skills of being able to do creative work, I think it requires an apprenticeship. So a Ph.D. in the best circumstances is more like an apprenticeship like one always had in any trade or art, "Guru-Shishya Parampara" as we used to say in India. It is still there in India in Indian classical music. People go to a guru, and then they spend years of hard work to build up the skills needed. There is a particular "Sadhana" I guess you would say, that you have to do and there are no shortcuts I think to that. So, I feel it is important to have this long period when you make a transition from being a student to researcher and be able to come up with new ideas by developing the skills and getting exposed to the knowledge already there. All these take time, and they don't come easily. So, if you want to do research and come up with profound ideas, I think some of these things are inevitable. So, in that way, I guess I'm a little more of a traditionalist. But of course, I think, sometimes, the Ph.D. system also gets abused as people often use Ph.D. students and postdocs in some of the subjects as essentially some kind of slave labor. I think that those sort of extremes and abuses of the system should not be there. But in the best case, it can be something like what I said - this idea of going through a certain period of "Sadhana" to develop your skills to grow as a musician or a researcher, whatever it is.

9. If someone wants to pursue a career in research in any of the top Indian or foreign universities, what would your suggestions be?

As I said earlier, I think research requires something very different from solving exams and doing problems in a time-bound way, which is what a lot of the coursework emphasizes, unfortunately. I mean, with these quizzes, mid-sems, and end-sems you're constantly being evaluated. You sit for two hours, and it's sort of a test of how much you have absorbed from the class, and it's the question of how you can apply some of the formulas and things you have learned and get out answers. I think it shouldn't be overdone. In research, it's a question of coming up with your own questions, exploring ideas, and developing a sense of what is interesting but at the same time, developing qualities of perseverance and willingness to do something, being regular, having stamina - not giving up and not getting demoralized. So, a lot of all these other qualities are also very important as a researcher, and one must understand that doing well in exams is not always the same as doing well with all these other skills.

So, if a person is interested in pursuing research, it would be good if the person, if not the system, at least the individual realizes that these are important things to develop and pay attention to these. For instance, I think you can distill the sense of any subject to a few essential key concepts. It's important to keep those in mind, understand those, keep thinking about them, and play with those in many different ways while you learn the subject. And of course, you need to solve problems, and develop that facility with solving problems. Still, you should pay attention also to the concepts because in the end, when you're stuck and in research, you're stuck most of the time, then you have to go back to concepts, revisit them, use them and find the basis of getting unstuck. So in an exam, you do things for one hour, you either know the answer to the question or not. The teacher has phrased a question that you know is a well-designed question, and you just need to find the answer to it, but Nature doesn't put things like that. In Nature, you have to ask the questions and try to figure out the answers.

So, not only in Physics, Mathematics or Computer science, in any kind of research, you have to nurture that creativity which comes from asking questions along with the other things, as I mentioned earlier, stamina, perseverance, the idea of not getting stuck and getting demoralized when you are stuck.Many people are good at solving problems quickly, but when you give them a long problem, which will require days, weeks, months, or even years to solve, they are not able to take it up because they can't focus or hold their focus on a problem for an extended period. In some ways, our system encourages this kind of ADHD-attention deficit because you are just pressurized to just do problems in a short period and that too a well-defined problem. So this other kind of skill should also be developed and encouraged.

Another aspect I think is learning to collaborate and work in teams because much science and research nowadays is collaborative, and teamwork is essential. You often have people with complementary expertise and skills, and bringing them together can really make things more than the sum of their parts. And this is one thing you realize when you see the institutions in the west that they are able to bring together people to work together in a very effective way such that they are always more than the sum of their parts and that's what enables a lot of breakthroughs to happen and so on because people are able to come together and from that new sparks fly. So this can be encouraged and built up even at the undergraduate level. I think some of it is done as there are group projects and so on, but I think more of that can be somehow encouraged.

Thanks,

Rajesh Gopakumar

Managed by - Aman Verma